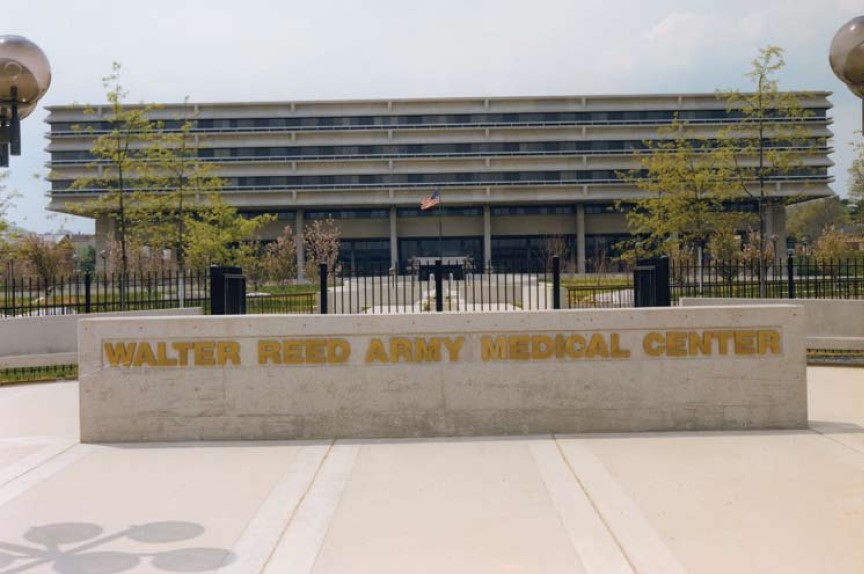

Overview

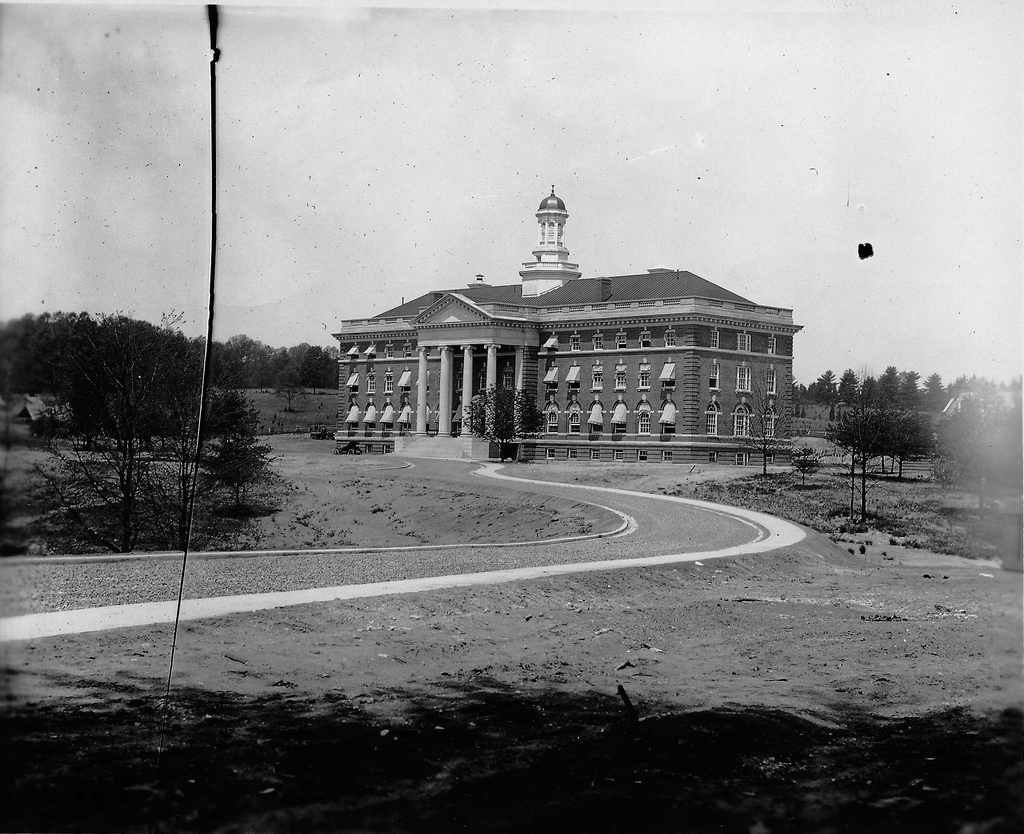

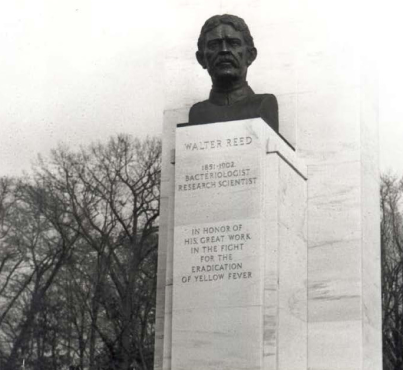

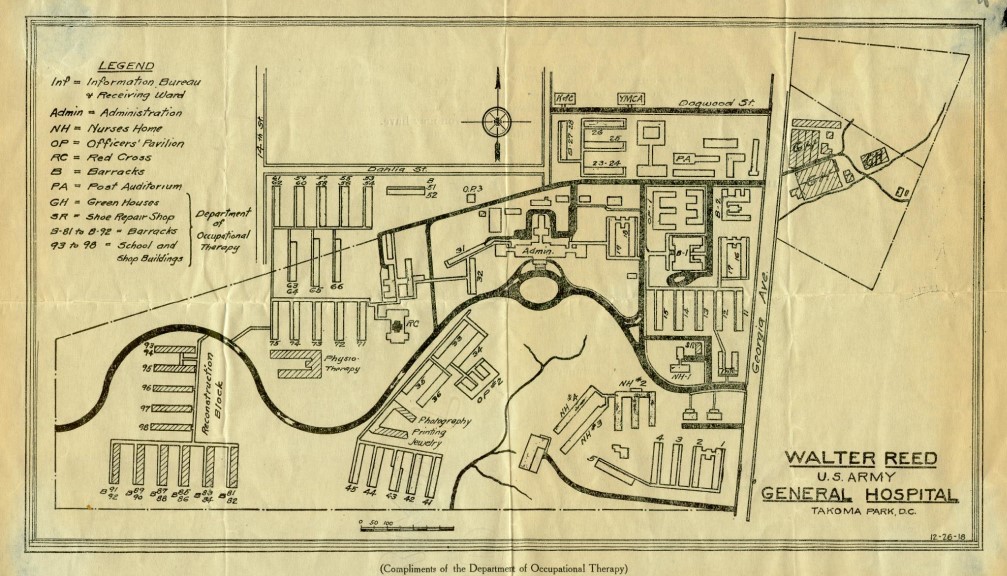

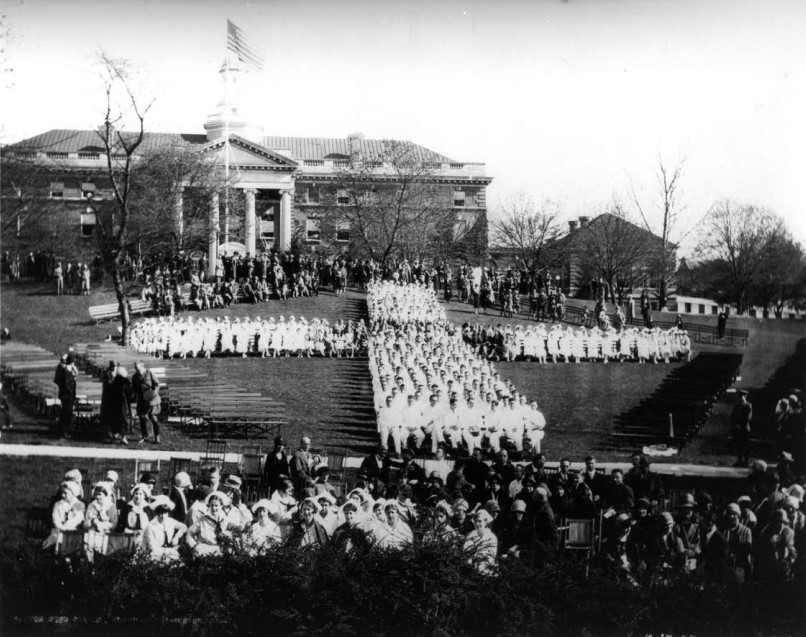

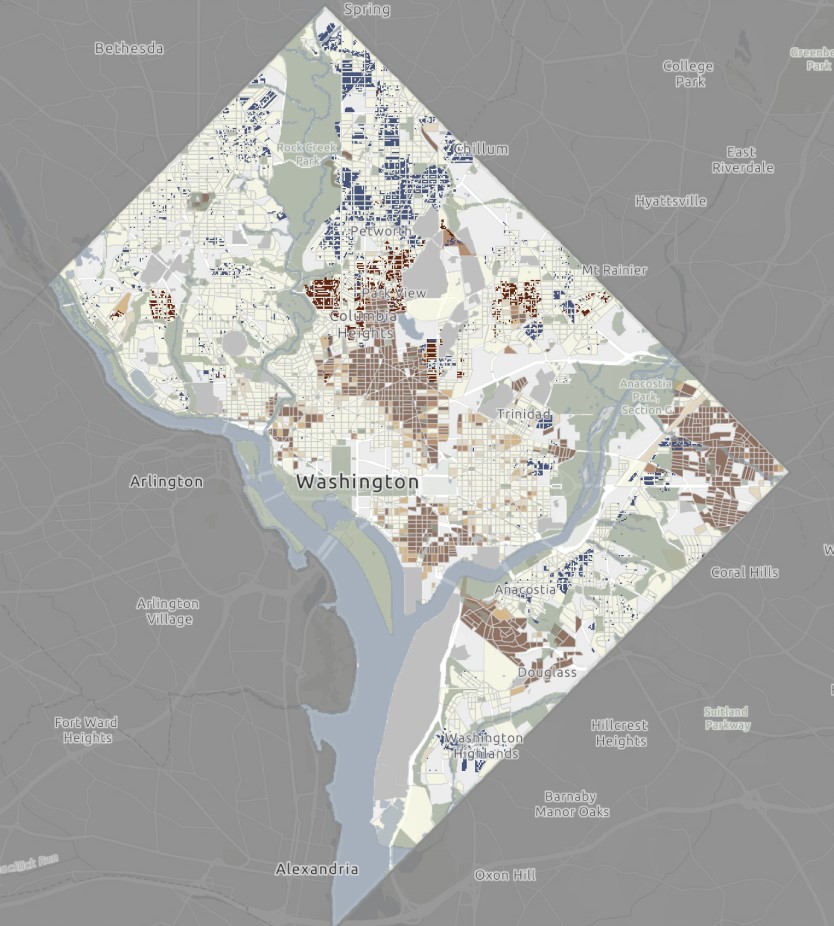

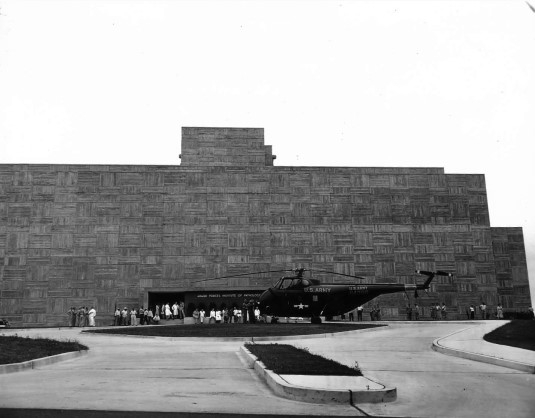

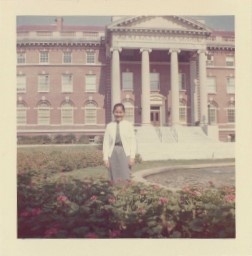

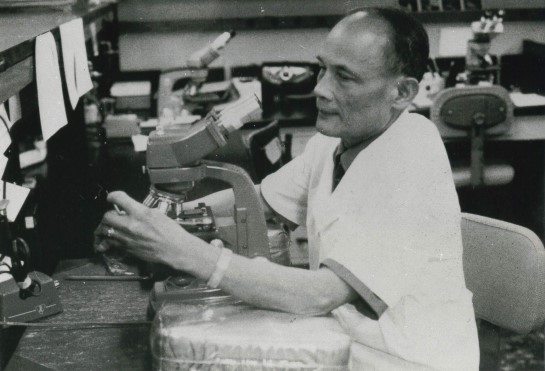

Breathe in the future at The Parks at Walter Reed — a green and growing District community that upends the ordinary. Formally the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, this 66-acre redevelopment redefines city living and brings the outdoors within easy reach. Upon completion, The Parks will encompass a total of 3.1 million square feet, combining various types of development, showcasing a harmonious blend of repurposed historic structures, newly constructed buildings, and a plethora of outdoor amenities interconnected by a series of parks and plazas. The Parks is an unexpected destination honoring the legacy of Walter Reed through the Master Development Team of Hines, Urban Atlantic, and Triden Development Group.